Victoria Lidiard (nee Simmons), the last known suffragette, died in 1992 at the age of 102. When I met her five years earlier she was still managing her roomy Brighton flat entirely on her own, a small, alert retired optician whose neighbours had no idea this sprightly old lady had once done time.

In March 1912 Victoria was gaoled for two months for taking part in one of Emmeline Pankhurst’s days of action. She’d travelled from Bristol to London to join a well-orchestrated campaign of disruption to protest at the Liberal government’s refusal to give women the vote. At a prearranged time suffragettes smashed windows all over central London. Victoria’s beat was Whitehall, her target the War Office. Extra policemen were on duty to look out for suffragette demonstrators. Appearing as demure as possible, Victoria deliberately walked in step with a policeman to allay suspicion. When she suddenly threw a stone through a War Office window, she was convinced he was taken completely by surprise.

A second policeman quickly rushed up to her, then a third. She was taken to Bow Street police station with a policeman grabbing each arm and one following behind. But Victoria had anticipated her arrest and had a plan to get rid of the evidence.

A second policeman quickly rushed up to her, then a third. She was taken to Bow Street police station with a policeman grabbing each arm and one following behind. But Victoria had anticipated her arrest and had a plan to get rid of the evidence.

“I had eight stones but I’d only used one, so on the way to the station I discreetly dropped them one by one but to my amazement when we reached Bow Street, the policemen who’d followed put the seven stones on the table and said, ‘she dropped these on the way.’” That was that.

Victoria spent the next sixty days in Holloway but remembers little of her time there. As a political prisoner she didn’t have to do prison work and there was nothing to do. She remembers the windows opened a crack to allow ventilation and her sister used to stand outside and she would shout messages to her. She did not go on hunger strike, largely because she had promised her formidable mother she would not. On her release she was awarded the suffragette brooch for bravery.

The enthusiasm for the cause came from Victoria’s mother who organised all her daughters into joining the suffragettes. She had produced 12 children at 13 month intervals of whom 8 survived. Victoria could not remember her mother ever having a good day’s health, but, though physically frail, she had an iron will and was a passionate believer in women’s rights. She and her daughters (opposed by her husband) were also fighting for proper education for girls and for the end of the white slave trade. Living in Bristol, Victoria’s family heard stories about girls being kidnapped and whisked down to the docks to be shipped away to slavery overseas. They were convinced this issue would continue to be ignored until women had the vote. They mostly campaigned in Bristol where they chalked messages on pavements, addressed meetings at the docks from the backs of lorries (Victoria said she was a hopeless speaker) and handed out leaflets. Victoria got used to being heckled, occasionally spat on and she was once shouted at by a clergyman who told her to get back to the kitchen.

When war broke out the movement lost impetus as its leaders went their separate ways. Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst became superpatriots while Sylvia sided with the pacifists. Victoria ran a guest house in Kensington for professional women with her sister and worked in munitions at Battersea Power Station. In 1918 British women were given the vote but only six million out of a total of thirteen million were actually enfranchised. Women over thirty who were householders, or wives of householders, or had been to university were allowed to vote. It wasn’t until 1928 that all women over 21 were finally allowed to vote.

In 1918 Victoria married Major Alexander Lidiard MC. He had, himself, been a member of the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement and they met while she was selling the magazine, Votes for Women. They both trained to be opticians, running separate practices but swapping one day a week for patients who preferred an optician of the opposite sex.

Over the years Victoria lost touch with her suffragette friends but never lost her passion for women’s rights. Right up to the end she was campaigning for the ordination of women which, she said, was ‘meeting with the same opposition as the fight for the vote. There is no physical, intellectual, moral, theological or spiritual reason why women shouldn’t be ordained.’ Two years after her death 32 women were ordained into the Church of England. Today one in five clergy are women.

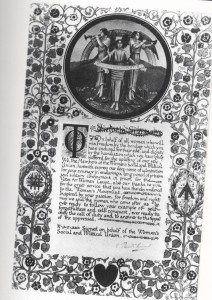

Victoria Lidiard’s certificate of thanks for her devotion to the cause, signed by Emmeline Pankhurst

Victoria Lidiard’s certificate of thanks for her devotion to the cause, signed by Emmeline Pankhurst

Afterword: I interviewed Victoria for the book and TV series, Out of the Doll’s House. It’s probably statistically irrelevant but it struck me how often fit nonagenarians, like Victoria, were life-long vegetarians…